Pixel Intensity

Introduction

So far, we've focused on binary images - images with only pure black or white pixels. But very few black-and-white images are like this - typically, these images have shades of gray.

How many? "Fifty!" I hear you say, teeth gnashing. No - not fifty. Not typically, at least. Most images have 256 values of gray available to them. But why this strange, completely un-sexy number?

Binary

Many* countries count using base-10 - that is, our 'places' on our numbers can hold 10 values. For instance, a single digit can be 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, or 9. Likewise, the 'tens' place can be 00, 10, 20...etc.

Aside: Wait...'many'?

Yep! While most countries do *math* with base-10, some languages speak using base-20. Apparently, Babylonian astronomers used base-60, which is why we have, for instance, 60 minutes in an hour, or 360 degrees in a circle. How neat is that!Computers, however, use base-2 - where each place is not represented by the number of fingers on both hands, but rather a single finger, or perhaps a switch being flicked either 'on' or 'off'.

But this is boring. Here's an example:

Some terminology. In computing, each place is called a 'bit', which is short for 'binary digit'. If you have (typically*) 8 of these, that's called a 'byte'. Less common, but certainly more whimsical, 4 bits are known as a 'nibble'.

Aside: Typically? Is nothing sacred?

No. Computing was/is kind of the Wild West, and standards tend to only come after enough blood has been spilt, if they come at all. A byte was originally a stand-in for however many bits it took to encode a letter in a computer, but apparently this was not consistent. In an alternate universe, we would be calling bytes 'slabs' (short for syllable) instead.You'll notice a couple things. First, it takes three places to represent 8 numbers (0-7), technically making binary more 'verbose'. You'll also notice that (like decimal numbers), the smallest place is on the right and the largest on the left.

Aside: Hey, why *are* the biggest decimals on the left?

I don't often work with binary, and whenever I do it feels 'backwards' - but it's technically the same direction as decimal. That brought me to the question...why do we do decimal this way? As best I can tell, this method of writing numbers originated from a language that was written right-to-left, and as best I can tell, in modern Arabic, despite it being a right-to-left language, the order of numbers is the same as in English.

That said, it doesn't make much sense to describe the merits of which direction it 'better'. Some have argued that putting the most significant number first allows you to detect magnitude, then get more granular as you read more digits, but this still requires reading all the digits to at least get the size of the number - so I'm not particularly moved by that argument. Smaller digits at the beginning only seem to make sense from a language perspective - that is, "growing" a number in the same direction that writing occurs.

Ultimately, something like scientific notation tends to circumvent this issue, particulalry for large numbers where keeping track of 6+ places becomes challenging.

But back to our shades of gray. As a little challenge, take no more than a minute or two to integrate the idea of a byte and the nature of binary and try to come up with why we might have 256 shades of gray.

...

You may have determined that if you have a byte, with 8 places available to you, you can represent all numbers 0-255 (that is, 256 values).

So we have 256 gray values available to us largely because it's tied to the definition of a byte. But is it *enough*?

Bit Depth: How many colors do you really need?

The question of 'how many shades of gray are enough' depends on the image. Obviously an entirely black or white image only needs one bit to represent it with perfect fidelity. On the other hand, there are infinite shades of gray in the real world so striving for perfection in all images is impossible.

Why not just use as many bits as possible?

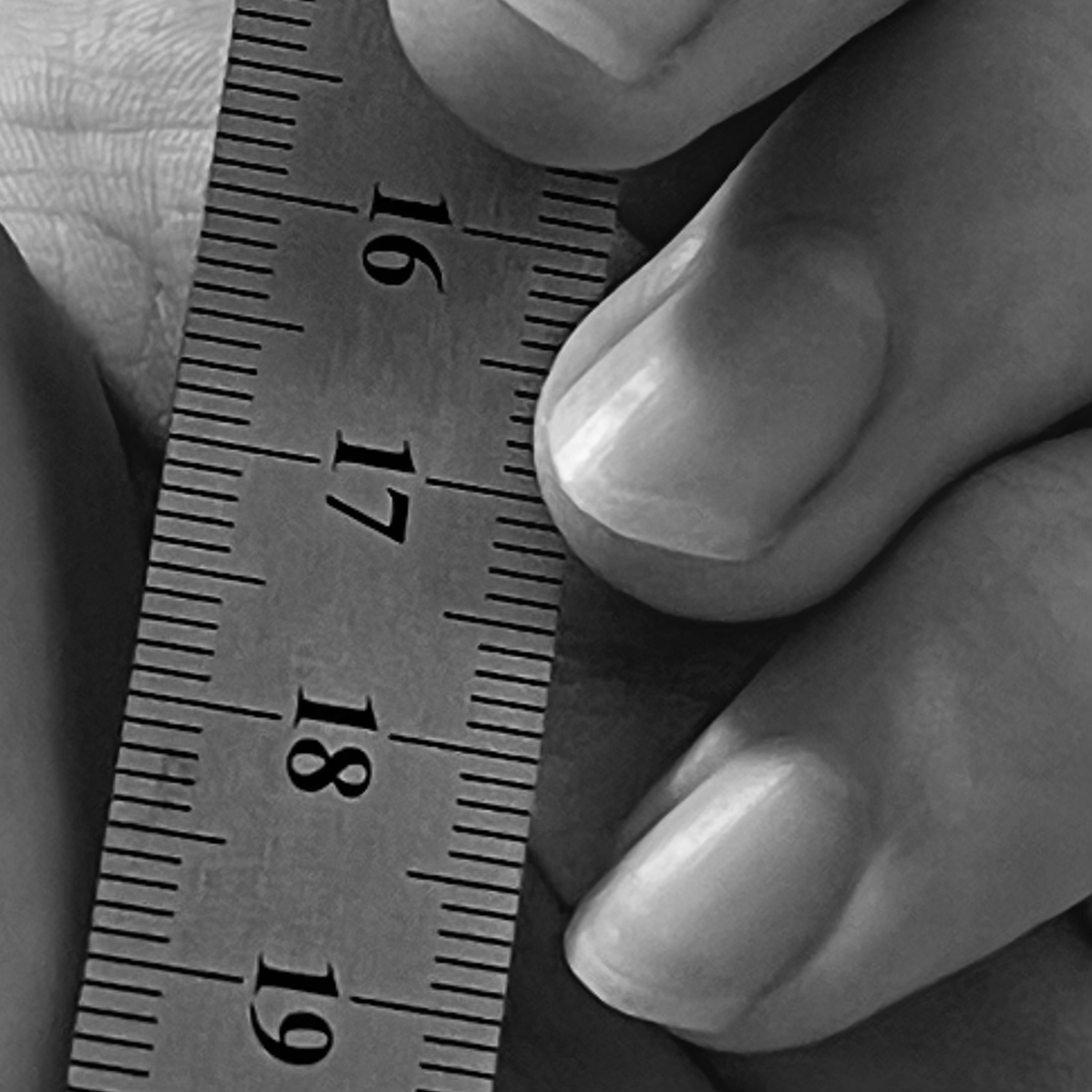

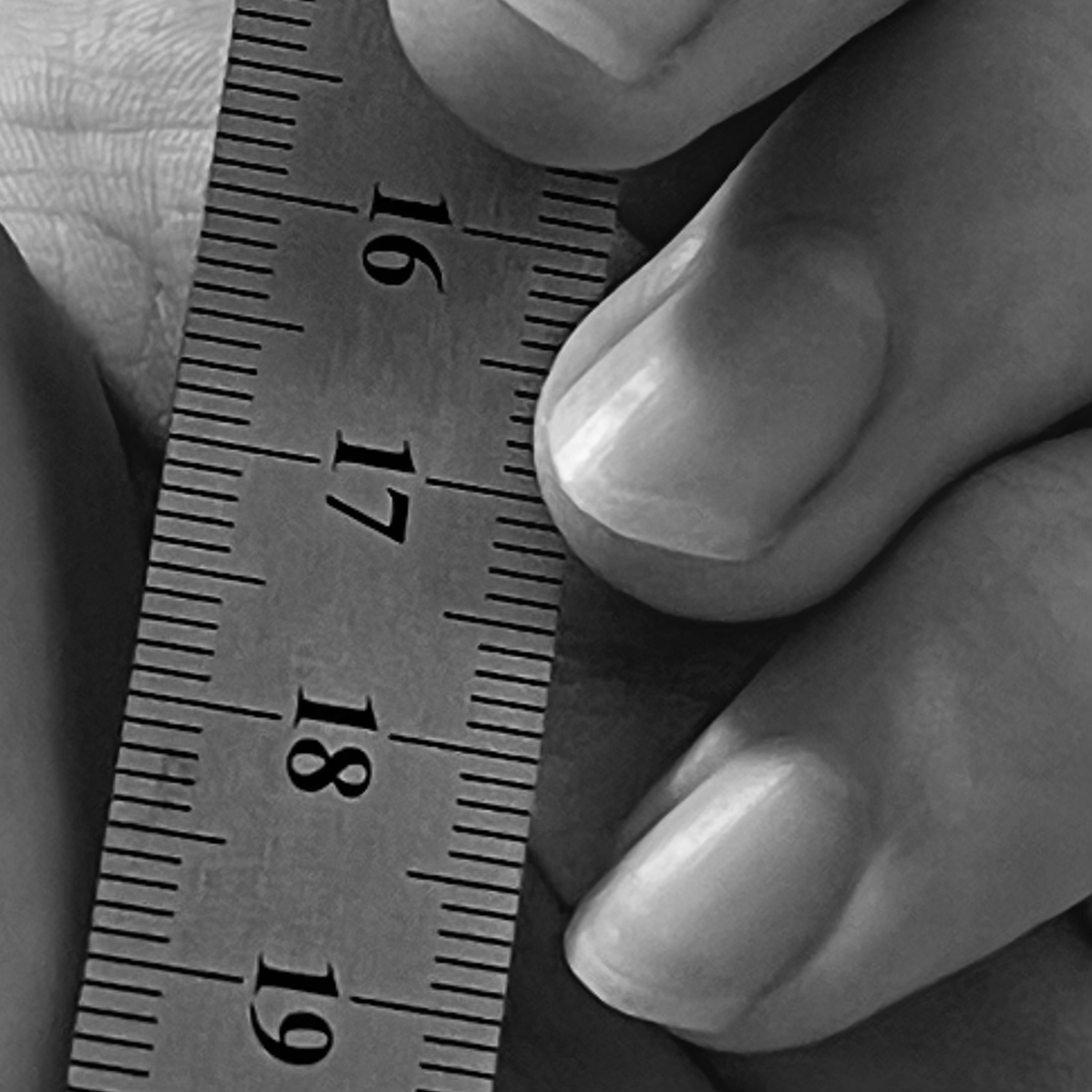

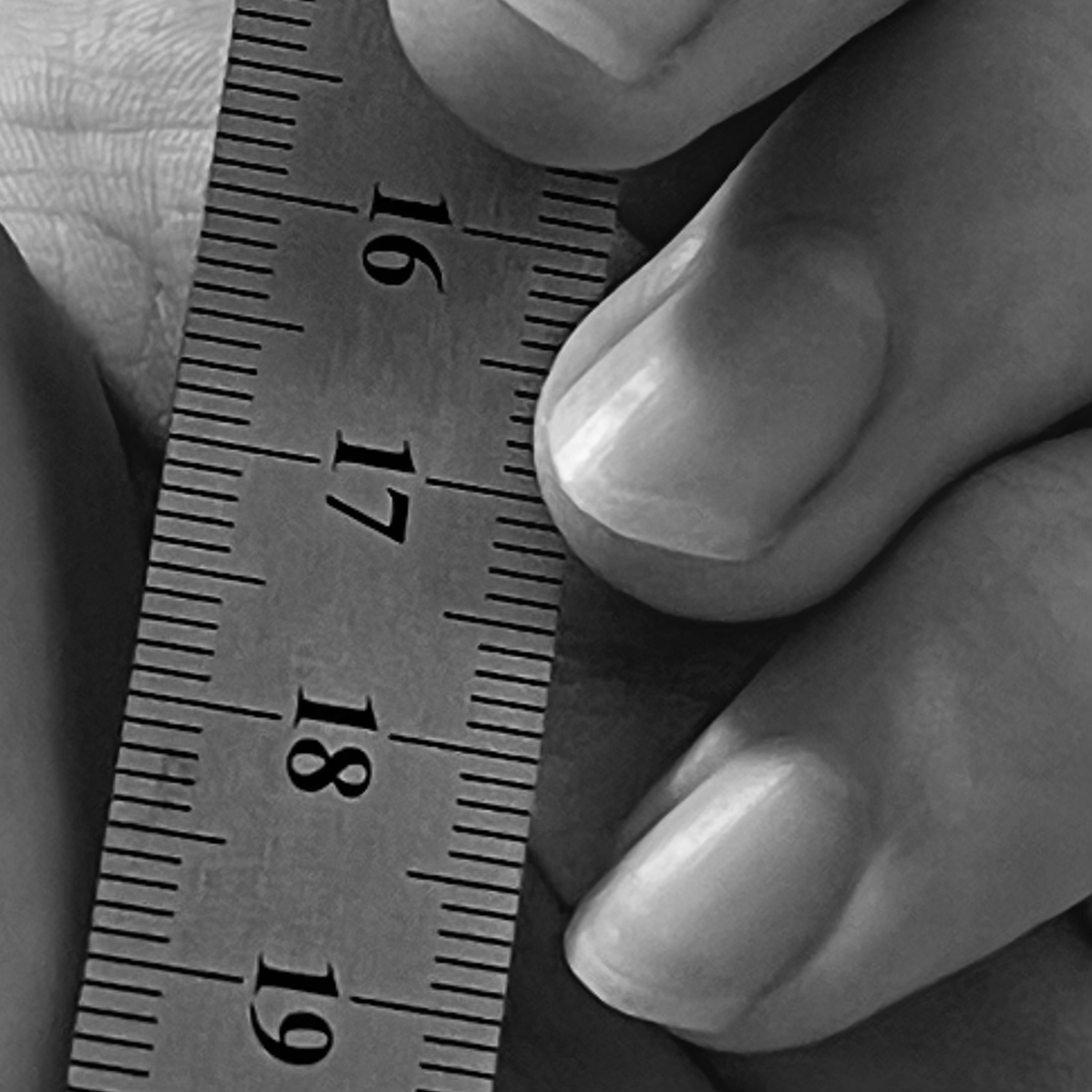

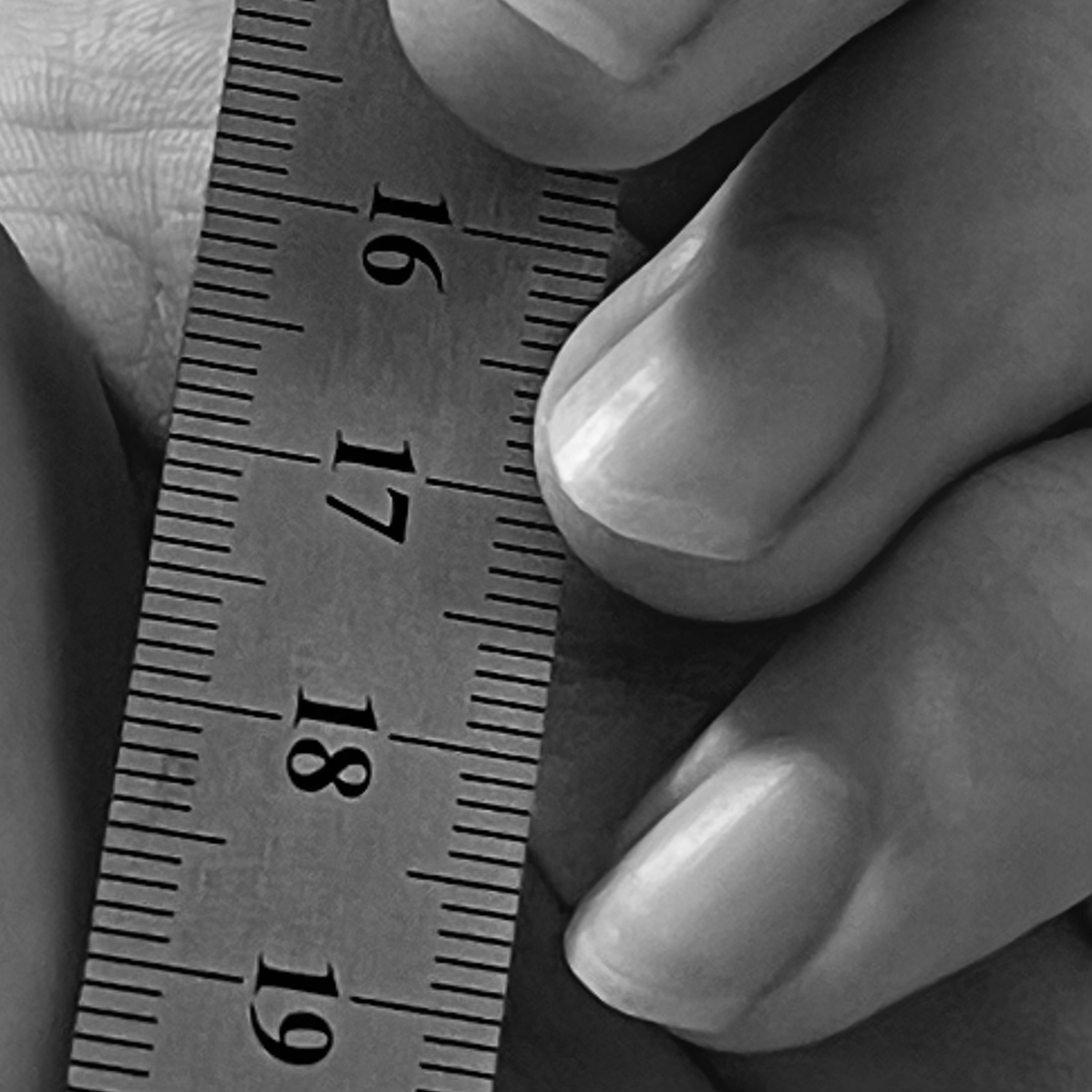

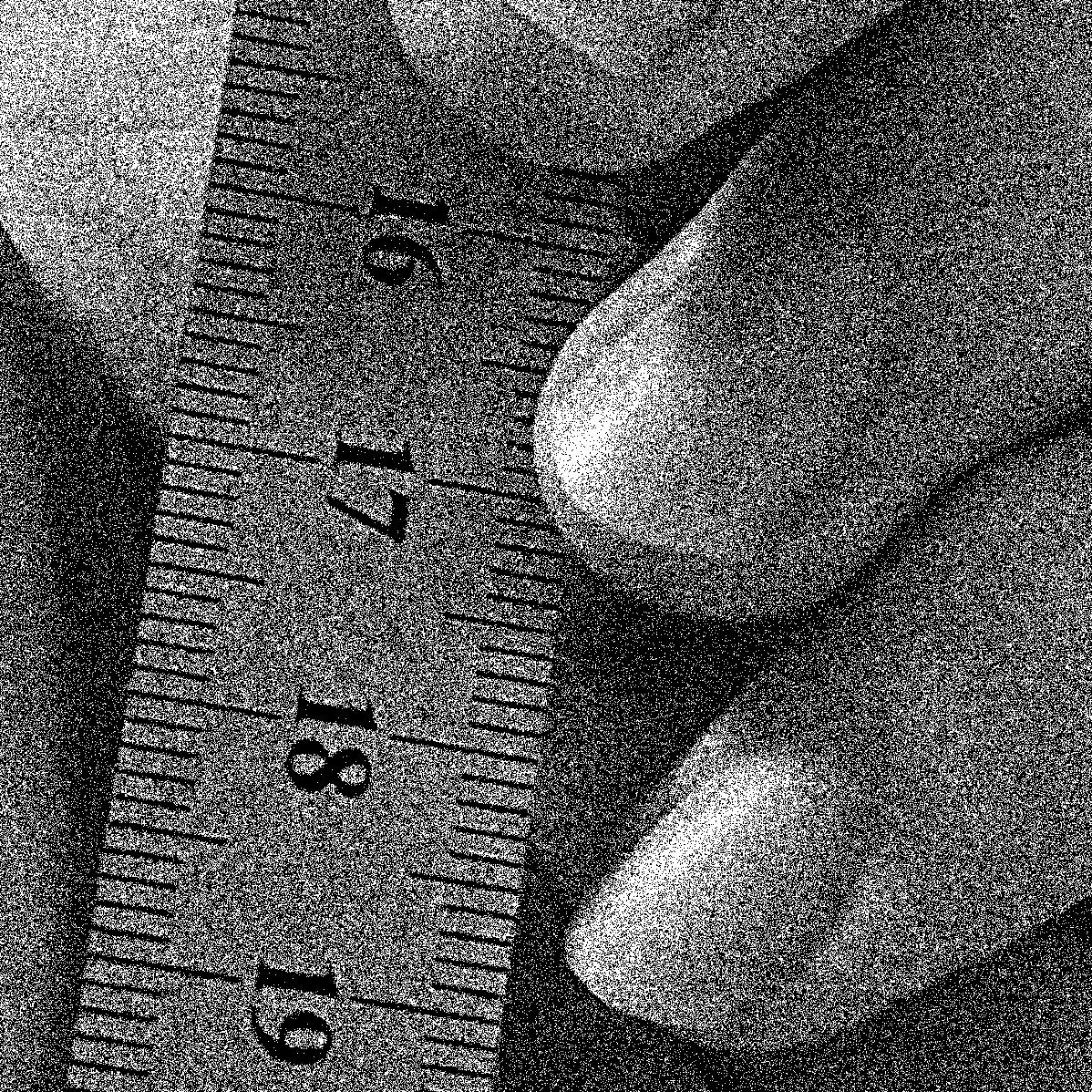

Image size on disk. If we don't take compression into account, each pixel in an 8-bit image takes up one byte of memory. The image of the hand with the ruler below is 1198x1198 pixels, or 1,435,204 pixels, all of which are one byte. This becomes 1434204/1024 = ~1402KiB or ~1.37MiB. Compare that to an image of the same size that is 1 bit, which would only take ~175KiB.

Practically, compression changes the game quite a bit. The original photo is a HEIF image, which compresses quite well. That means that the original image is not 1.37MiB, but 129KiB (~10x smaller). The JPEG that I converted it to is 493KiB, and that smooshes down to only 99KiB when converted to 1 bit. Clearly, some 'compression math' is going on behind the scenes. That said, the point remains: Bits aren't free.

Let's be simplistic but pragmatic, focusing on an image of just a single pixel. Below is an interactive example where adjusting the counter adjusts the brightness. Let's start with 3 bits:

You can already tell that this isn't exactly the smoothest transition between steps, but let's make it a little more clear by adding a pixel of one lower and one higher intensity to the left and right:

How many bits does it take until things look smooth? Go ahead and take the reins - adjust the bit depth below the intensity slider and see if/when you can no longer tell the difference between one pixel and its neighbors:

With my display and my eyes, I can still make out a difference even with all 8 bits, particularly at the lower intensities (human brightness perception tends to be logarithmic - so equally spaced jumps at lower brightness tend to look bigger than at higher brightness). So for this very synthetic case, no - 8 bits doesn't seem to be enough. But in my opinion, it's pretty close to enough.

But let's be more practical and use a real image:

Nice, right? Especially after seeing nothing but binary images, 256 shades of gray is quite a lot to work with. Just to tie it back to the numbers, let's zoom in really, really close.

We've zoomed in somewhere in the center of the image, and I've overlaid the intensities on this tightly cropped section. Really, that's what this image is: an array of intensity values from 0-255.

But back to the question at hand: how many bits could we reasonably use to represent *this particular* image? We can be qualitative.

You'll notice that the sufficiency of bit depth depends on:

- The intent of what you want to do with the image. If you just need to know the gist, 2 or even 1 bit might do, but if you want to hang it in a gallery, you want as many bits as possible.

- The subject matter. The ruler only needs a few bits to look pretty much normal, whereas the smooth transitions of the hand need more

An aside: Translating Bit Depths

This is a problem I didn't even consider until writing this post. How do you convert from one bit-depth to another?

To illustrate my quandry, look at this plot:

Going from bottom to top is fine: poke your finger at any shade of gray and drag it upwards. That's your new gray value.

However, going from a lower bit-depth to a higher bit-depth leaves some ambiguity. Depending on where you point to in a given gray box, you'll have different options. Even worse, you can't just stick with the same shade of gray that you had in the previous palette to use in the new bit-depth palette, because it might not exist in the new palette!

For instance, look at the two middle gray-values in the 2-bit-depth row. These values don't match any colors below them exactly. So which do we choose?

I genuinely don't know what the industry standard is supposed to be, but I'll tell you what I'm going to do: When given a choice between many values of gray, choose the most 'outside'. For instance, if I was converting from 2-bits to 4-bits, 01 would become 0100 and 10 would become 1011. This has the advantage of keeping '0' as '0' and '1' as '1' regardless of how many bits we traverse.

Bonus: A quick conversion algorithm

This conversion can be done quickly and easily like so:- Start with some intensity at some bit depth (let's say 0101)

- Look at the leftmost digit (here, 0)

- Add that number to right side as many times as you need to get to the correct number of bits (so moving to 8 bits would be 01010000)

Slicing Bits

There's another way of looking at this - rather than sorting whole intensity values into an increasing number of 'buckets', what if we look at each bit as its own image? Like, what if instead of treating each image as a collection of 8 bits, we instead thought of an image as a stack of 8, 1-bit images? To illustrate the principle, let's start with a 3-bit image becoming 3, 1-bit images:

The image on the left is our original image, and the three images to its right represent different bits in the 'stack'. In those three images, the pixels are black if that bit 'place' is 0, and is white if that bit place is 1.

As with decimal numbers, as we move to the right, the value of the bit matters less for the overall magnitude of the value, so we would expect our first 'slice' to look the most like our image, and the next few slices to look less like the original. We can see that's sort of the case with the synthetic image above, but it's difficult to tell with so few bits.

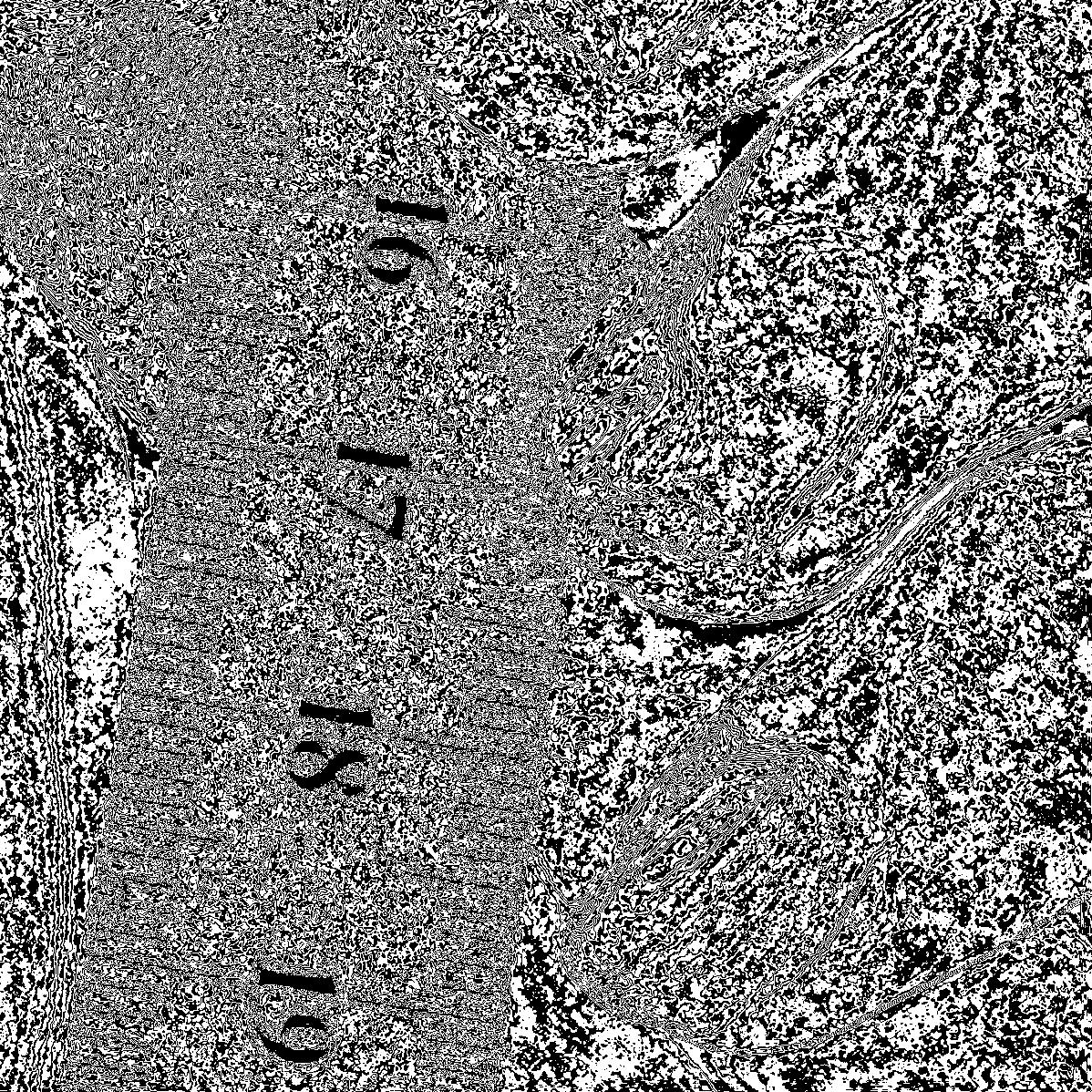

Let's apply this same principle to our full, 8-bit image:

(Here, when I say 'Bit 8', I mean the most significant, left-most bit in a byte)

Some things that might jump out at you:

- The slice with the 8th bit looks exactly like our 1-bit image above

- As you go to less and less significant bits, you slowly sink into a sea of noise.

This view of our image helps explain why we didn't see much change for the last couple bits in the bit-depth examples above: they were mostly contributing noise. It ALSO shows us regions where we can expect to see the most change per bit-depth: the ruler for the first couple bits, the fingers for the next few bits. In fact, were we to recombine these images layer by layer (translating the intensities as necessary), it would look nearly identical to the bit-depth examples above.

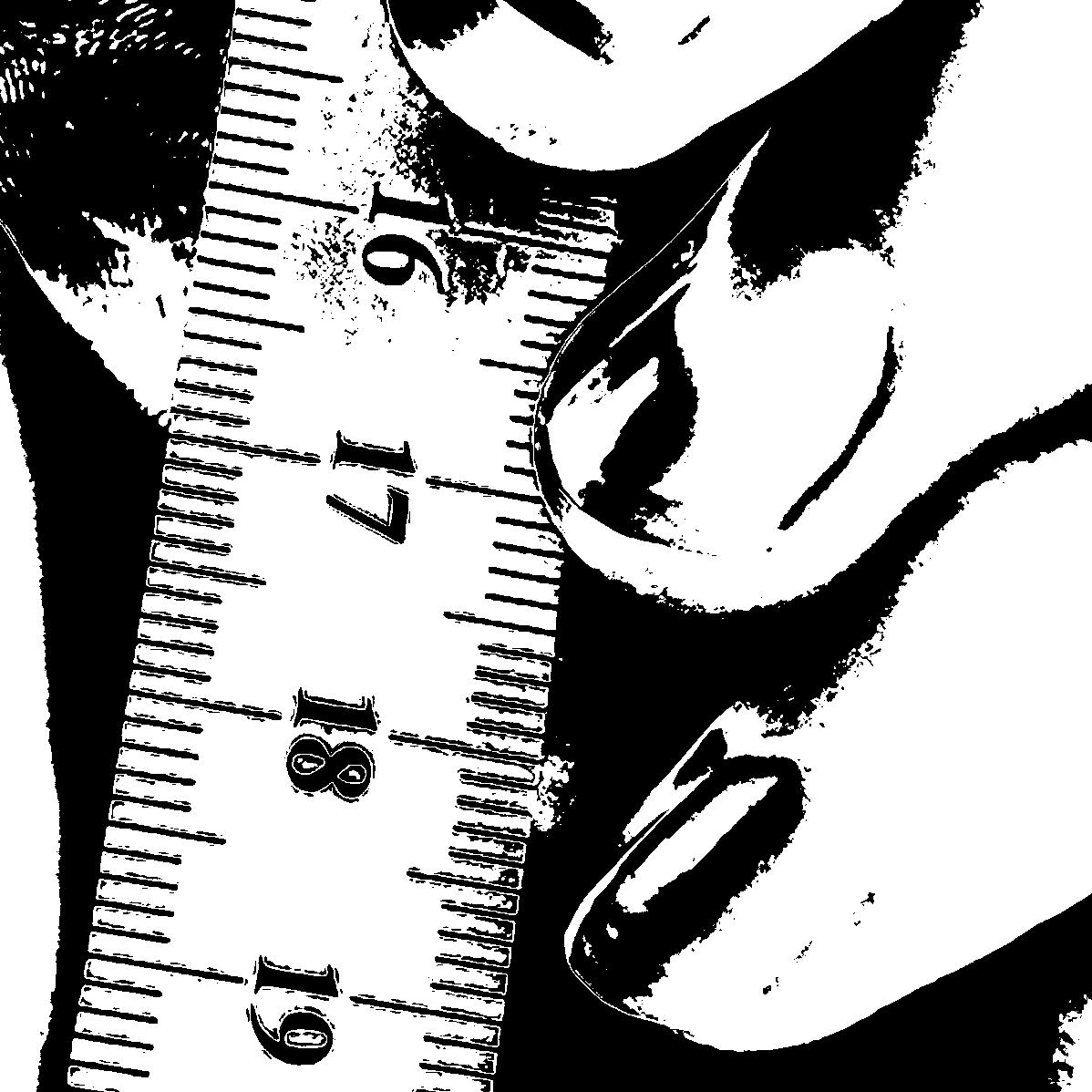

Intensity As A Probability

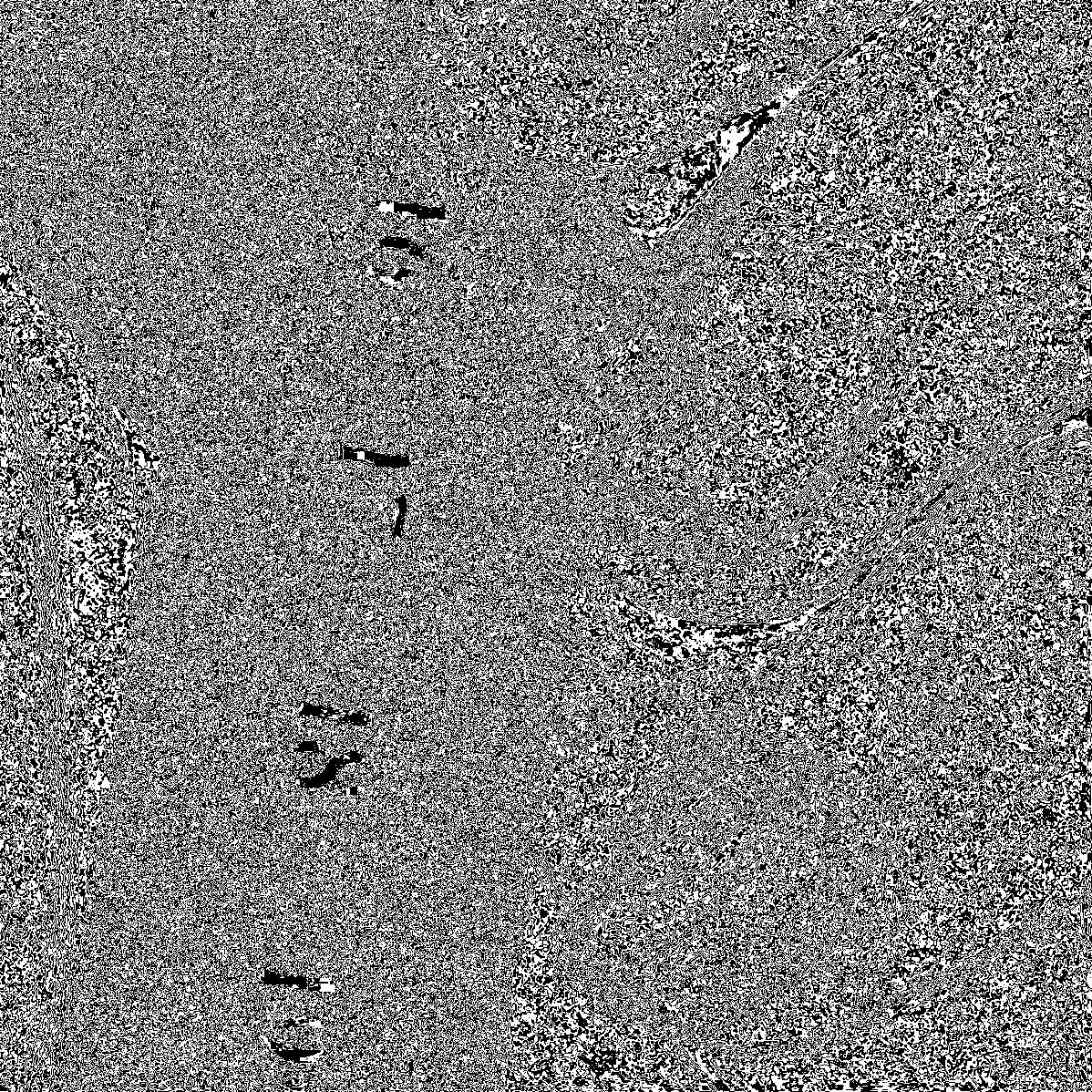

Finally, for a bit of fun. When converting to 1-bit, what if we treated intensity of a pixel in the original image as the probability of the 1-bit image having a white pixel at that location? For example:

- If a pixel in the original image had an intensity 255, it would have a 255/255 * 100% = 100% chance of being a white pixel.

- If a pixel in the original image had an intensity 106, it would have a 106/255 * 100% = ~42% chance of being a white pixel.

Both images are using only just pure black and pure white, but the probability-based version captures much more detail, essentially simulating grays via stippling. The problem? This is immensly hard to compress, leading to a much larger image size. Were it not for compression, both these images would take up the same amount of storage. However, as it stands this image is nearly 10x time size of the 1-bit 'threshold' image, and nearly 2x the size of the original image! Still, it's quite a neat way to think about mapping intensities.

FIN

Hey thanks for reading. I learned a lot writing this, hope you learned a little reading it. The idea of pixel intensity isn't too terribly complex, but it's foundational to when we start doing math on images. In the next chapter, we'll do exactly that. Intensity filters, which do math on a single pixel at a time (not taking its neighbors into account), will be our first foray into such things. See you then!